Nadav Kander (born 1961) is a London-based photographer, artist and director, known for his portraiture and landscapes. Kander’s photographs are often described as quiet, monumental, and imbued with a sense of unease. They are landscapes, portraits, and still lifes, but rarely straightforwardly so. A Kander image is less a record of a thing seen and more an exploration of the psychological space between the viewer and the subject, between the present and an imagined future. He photographs the vast and the minute, the industrial and the natural, the powerful and the vulnerable, finding in each a similar thread of human fragility and the precariousness of our place in the world. Kander’s work is less about the decisive moment and more about the lingering aftermath, the quiet before the storm, or the slow erosion of time. A sense of quietude and introspection permeates all his work, from his vast landscapes to his intimate portraits, connecting these seemingly disparate genres. As Kander himself has stated, “I’m looking to be moved by the image and I hope for the viewer to recognize something of themselves in the image too.”

Kander has cited a diverse range of influences, from the stark landscapes of the American West photographers like Carleton Watkins and Timothy O’Sullivan, to the painterly atmospheres of early pictorialists. He has spoken of the impact of the Bechers’ typologies of industrial structures, not for their detached objectivity, but for the inherent human presence that resonated in their stark depictions of functional architecture. One senses, too, the influence of photographers like Edward Weston, whose close-ups of natural forms revealed an almost abstract beauty, and the quiet intensity of Irving Penn’s portraits. “I’m interested in the space between things,” Kander has said, “not just the thing itself.” This interest in the interstitial, the in-between, is evident in his landscapes, which often feature liminal spaces – shorelines, riverbanks, the edges of cities – places where human activity and the natural world collide and intertwine. This fascination with the “space between things” extends to his portraiture, where he seeks to capture not just a likeness but the unspoken stories and emotions that reside within his subjects.

The importance of Kander’s work lies in its ability to evoke a sense of unease and wonder in equal measure. He photographs the detritus of industrial progress – abandoned factories, decaying machinery, polluted landscapes – not with a sense of moralising condemnation, but with a quiet acknowledgement of the human cost of progress. His images of the Namibian desert, for example, are not simply beautiful landscapes; they are also a reminder of the vastness of time and the insignificance of human endeavour in the face of geological forces. In his series "Dust," which documents the remnants of Soviet-era military installations in Kazakhstan, the crumbling concrete structures become monuments to a failed ideology, their decay a poignant reminder of the transience of power. “I’m drawn to things that are on the edge of disappearing,” Kander has explained, “things that are holding on, but only just.” This sense of impending loss, of a world in flux, is a recurring motif in his work, imbuing even his most serene landscapes with a subtle tension.

Over the course of his career, Kander’s work has evolved, but his core concerns have remained constant. He has continued to explore the relationship between humanity and the environment, the fragility of human existence, and the passage of time. His early work was often characterised by a stark, almost minimalist aesthetic. As his career has progressed, his images have become more layered and complex, incorporating a greater sense of narrative and emotional depth. His series "Yangtze, The Long River," which documented the rapid industrialisation of China, marked a turning point in his career. The series was not simply a record of environmental destruction; it was also a meditation on the human cost of progress and the loss of cultural heritage. “The Yangtze project was a huge undertaking,” Kander has said, “it changed the way I thought about photography.” This project, which saw him travel the length of the Yangtze River over three years, solidified his reputation as a photographer capable of tackling complex and globally relevant themes.

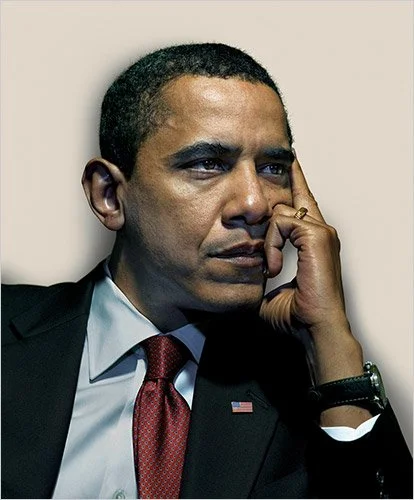

Kander’s portraiture too is compelling, and it forms a significant part of his oeuvre. Spanning 30 years and encompassing a diverse range of subjects, from world leaders to ordinary individuals, his portraits reveal a remarkable sensitivity to the human condition. As evidenced in The Meeting, a recent volume dedicated to his portraiture, Kander’s lens captures the essence of his subjects, revealing their vulnerabilities, their strengths, and their place in the world. He has photographed Barack Obama, Sir David Attenborough, David Lynch, Desmond Tutu, Thom Yorke, and even his own mother, finding the common thread of human experience that connects them all. His portraits are not about capturing a likeness, but about revealing something of the subject’s inner life, their character, their anxieties, their place in the world. He often uses a shallow depth of field, blurring the background and focusing attention; notable too, is his use of coloured lighting, his subjects often bathed in a cinematographic blue/green haze spotted with warm notes of amber or pink or isolated from plain backgrounds by the corona-like halo of a ring flash. These techniques always drawing the viewer into a more intimate encounter with the individual portrayed, emphasizing their presence and suggesting a degree of psychological isolation. It’s not just about the face, though; sometimes a hand gesture, the way a person holds their body, or the space around them becomes just as important as the features themselves.

Kander’s portraits often possess a stillness, an intensity that invites contemplation. He captures moments of introspection, of weariness, of quiet strength. There’s a sense of something unsaid in many of his portraits, a story hinted at but not fully revealed. He avoids the posed, the performative, seeking instead the unguarded moment, the flicker of emotion that betrays the carefully constructed facade. In his portrait of Barack Obama, for example, the then-Senator is shown in a moment of quiet contemplation, his gaze averted from the camera. The image is not about power or status, but about the weight of responsibility and the solitude of leadership. It’s a portrait that humanizes a figure often seen as larger than life, revealing a moment of quiet vulnerability. This vulnerability is not weakness, but a recognition of the burdens carried and the decisions faced. This ability to find the human within the powerful is a hallmark of Kander’s portraiture.

Kander brings the same level of attention and insight to his portraits of ordinary individuals, finding the extraordinary in the everyday. The Meeting includes portraits of Walthamstow market traders, capturing the character and resilience of these individuals within their working environment. These portraits, like those of the famous, possess a quiet dignity, a respect for the individual and their experiences. They remind us of the shared humanity that connects us all, regardless of status or background. In these images, the individual becomes representative of something larger, a microcosm of the human condition. Kander’s own history informs his approach to portraiture. Having grown up in South Africa, his series of portraits of children in colonial school uniform, taken in 1991, are particularly poignant. As he reflects on one of these portraits, Schoolgirl (white photographer), he acknowledges the complex dynamics of the encounter, recognizing in the child’s gaze not mistrust, as he initially perceived, but disgust. This self-awareness, this willingness to confront his own biases and preconceptions, is what gives his portraits their depth and resonance. “A portrait is not about what someone looks like,” Kander has said, “it’s about who they are.” It's about the stories they carry, the experiences that have shaped them, the emotions that flicker across their faces.

Kander’s books are an integral part of his artistic practice, his first, Pentimento, published in 2000, was a retrospective of his early work, showcasing his diverse range of subjects and styles. Yangtze, The Long River, published in 2007, was a landmark publication that brought him international acclaim. Dust, published in 2011, continued his exploration of the relationship between humanity and the environment. Bodies. Still Life, published in 2016, explored the human form in a series of intimate and often unsettling images. The Meeting, his 2019 portrait collection, adds another important chapter to his body of work. “A book is a different experience than seeing a photograph on a wall,” Kander has said. “It’s a more intimate and immersive experience.”

Kander’s work fits into the history of photography in a number of ways. He is part of a tradition of landscape photography that stretches back to the 19th century, but his approach is distinctly contemporary. He is not simply documenting the world around him; he is interpreting it, imbuing it with his own vision. His work also engages with the history of portraiture, but he moves beyond the simple capturing of a likeness to explore the inner lives of his subjects. Kander's work shares some concerns with the New Topographics movement of the 1970s, which focused on the altered landscape, though his work possesses a greater degree of emotional resonance than the often detached work of those photographers. He is also part of a lineage of portrait photographers who seek to capture more than just an outward appearance, delving into the psychological depths of their subjects. "I'm not interested in just documenting reality," Kander has said. "I'm interested in exploring the underlying emotions and anxieties that shape our experience of the world." This exploration of the emotional landscape, both internal and external, is what sets his work apart.

Kander’s approach to landscape photography, his use of portraiture, and his interest in the relationship between humanity and the environment have all resonated with a new generation of artists. His work has also helped to broaden the definition of what photography can be, moving beyond the purely documentary to embrace a more poetic and expressive approach. His success in both the commercial and artistic realms, shooting covers for influential publications while simultaneously pursuing his personal projects, also provides a valuable model for aspiring photographers. As he notes, “I don’t think one gets ‘discovered’—rather, it happens for those individuals who fight to have their work seen.” His own career trajectory, marked by dedication, self-reflection, and a constant striving to refine his craft, serves as an inspiration to those navigating the often-challenging world of photography.

Kander has created a body of work that is both beautiful and thought-provoking, challenging us to consider our place in the world and the impact of our actions. His images are not simply records of the present; they are also glimpses into the future, warnings about the fragility of our planet and the precariousness of human existence. He asks us to consider not only what we see, but also what we don't, the spaces between the things, the emotions that flicker across a face, the stories whispered by a landscape. “I hope that my work can make people think,” Kander has said. “I hope that it can make them question the world around them.” His photographs are not easy or comfortable. They ask us to confront difficult truths about ourselves and our world. Yet, it is in this confrontation that the power of Kander’s work lies. It is a power that will continue to resonate for generations to come, prompting reflection, inspiring dialogue, and reminding us of the shared humanity that binds us all. His ability to bridge the gap between commercial and artistic photography, his dedication to mentoring young photographers, and his unwavering commitment to exploring the complex relationship between humanity and the environment all contribute to a legacy that extends beyond the individual image, shaping the future of the medium itself. He reminds us that photography is not just about capturing a moment, but about engaging with the world, questioning our place within it, and striving to understand the human condition in all its complexity and beauty.

"We are all on this earth for a very short time," Kander has reflected. "Photography is a way of trying to make sense of that." This sense of time, both fleeting and monumental, is a constant presence in his work, reminding us of our own place within the larger narrative of existence.