Stephen Shore, a photographer whose quiet, observant vision has profoundly shaped our understanding of the American landscape, holds a unique position in the history of the medium. He's not a purveyor of the spectacular or the conventionally picturesque. Instead, he finds a quiet poetry in the everyday, revealing the extraordinary within the seemingly mundane. His early colour photographs, in particular, are characterized by a remarkable stillness, a precise attention to detail, and a deep appreciation for the vernacular. Gas stations, parking lots, roadside motels, and the interiors of unassuming diners are all treated with the same level of visual consideration typically reserved for more traditionally "beautiful" subjects. Often devoid of human figures, his images nevertheless speak volumes about contemporary life, the spaces we occupy, and the subtle shifts of time. They prompt contemplation, not through dramatic statements, but through a gentle, insistent invitation to look. Shore’s photography is less about the what and more about the how of seeing. He has expressed a fundamental interest “in the world, in how things look,” a deceptively simple statement that gets to the heart of his artistic project. He doesn’t impose meaning onto the world; he seeks to understand and articulate his own way of seeing it. His photographs are less about the objects they depict and more about the very act of perception.

Shore’s influences are diverse, spanning both photography and other artistic disciplines. He has cited Walker Evans as a significant inspiration, acknowledging the impact of Evans’s documentary approach and his ability to find beauty in the ordinary. He has also mentioned being influenced by both good and bad photography as a young man, including commercial photography magazines like Popular Photography. As a teenager, he even contacted Edward Steichen at the Museum of Modern Art, showing him his work. Steichen purchased three of his photographs. “I think I didn’t know any better. I didn’t know that you weren’t supposed to do this,” Shore explained. He described those early photographs as “not really very good,” and acknowledged other, less celebrated influences alongside Evans. “I had a lot of bad influences also. Aside from the good influences, like Walker Evans, I looked at the commercial photography magazines, as well.” These included publications like Popular Photography, demonstrating a wide-ranging curiosity and an openness to different visual languages. While Evans primarily worked in black and white, Shore embraced the potential of colour photography early in his career, recognizing its capacity to capture the subtle nuances of light, texture, and atmosphere. This choice, at a time when black and white was still the dominant mode for “serious” photography, was a bold move that distinguished Shore’s work. He also shares a sensibility with the New Topographics photographers, including Robert Adams, in their shared focus on the contemporary landscape, though Shore’s work is less overtly driven by social or political critique. His perspective is more purely observational, less concerned with explicit judgments about the environment.

The importance of Shore’s work lies in its quiet subversion of photographic conventions, its subtle recalibration of how we perceive the world. He challenged established ideas about what constituted a suitable subject for photographic representation, elevating the commonplace to the realm of art. His images aren't about the spectacular or the sensational; they are about the act of looking and the process of reflection. They encourage us to decelerate, to attend to the details we so often overlook, and to discover the inherent beauty of the everyday. His photographs, as he describes them, “were not about what was in front of me, but about my experience of it.” This emphasis on subjective experience, coupled with a sharp awareness of formal elements, allows Shore’s images to resonate on multiple levels. They are simultaneously descriptive and evocative, capturing the specificities of a particular time and place while hinting at larger themes of cultural identity, memory, and the very nature of human perception. He also challenges the tendency to categorize photography into rigid “isms,” suggesting that a single photograph can function in multiple ways: as an art object, a document, a formal exploration, and a resonant expression on a deeper, more personal level. “Why can’t a photograph be all four things at once?” he proposes.

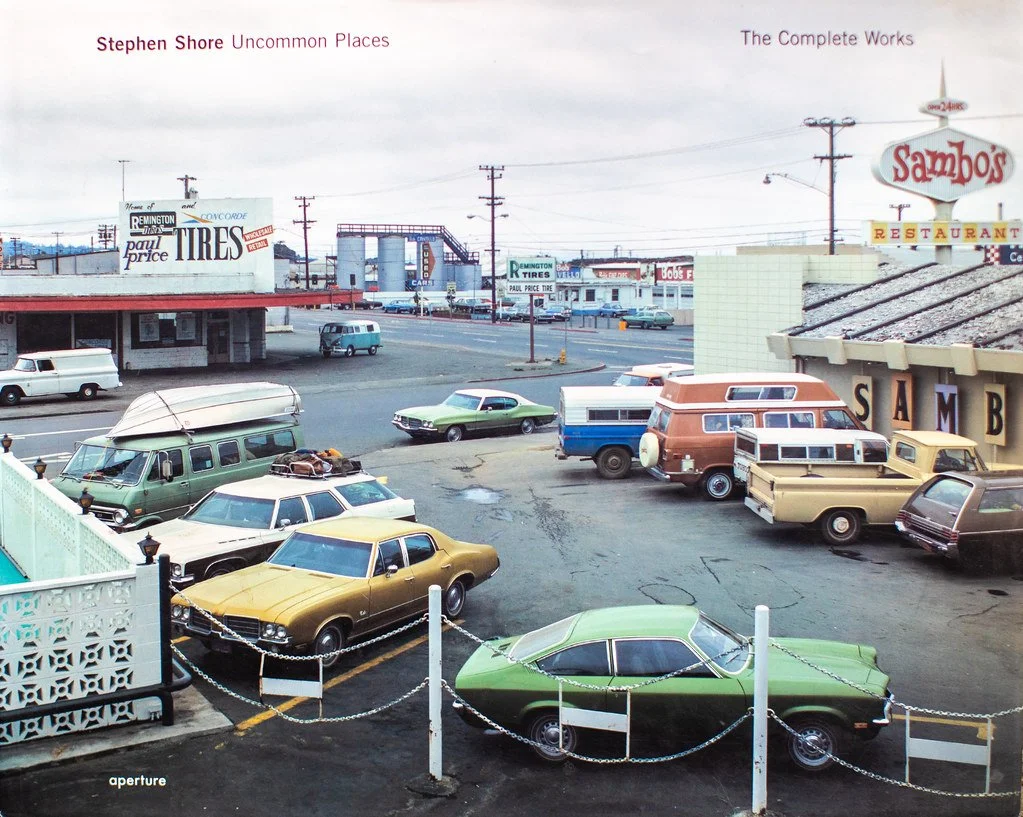

Shore’s artistic trajectory has taken him from his initial explorations of the American landscape to a variety of other subjects and approaches. He has worked with portraiture, still life, and even ventured into abstraction, always maintaining his unique sensitivity to detail and his commitment to observation. However, it is his early work, particularly the series “American Surfaces,” that remains most iconic and influential. These photographs, made during a series of cross-country road trips in the 1970s, capture a specific moment in American history, a period of change and transition. They provide a portrait of a nation in flux, a visual record of the ordinary landscapes that shape our collective experience. “American Surfaces” was initially shown as small, Kodak-processed snapshots, before Shore decided to create larger prints. He found the 35mm film too grainy for the enlargements he envisioned and thus transitioned to a 4x5, and then an 8x10 camera. “It was never my intention to go to an 8x10,” he explained. “I mean it really was simply that I wanted to continue American Surfaces but with a larger negative.” He discovered that the larger format led him to “discover other things about photographic seeing that I wanted to explore.” This marked the beginning of a “kind of formal evolution” in his work, an unexpected development driven by a process of inquiry that unfolded as he worked. The view camera, with its ground glass and the necessity of using a tripod, pushed him towards more deliberate decisions about composition and framing. “You can’t sort of stand somewhere, and it is exactly where you want to be,” he observed. This methodical approach, combined with the expense of film and processing, fostered within him “a kind of taste for certainty.” He also reflected on his time at Warhol’s Factory, noting the work ethic and openness of Warhol’s artistic process. “Andy was very open about his process,” Shore recalled. “What I saw every day was someone making aesthetic decisions.” He observed that while his commercial work taught him the value of collaboration, his personal artistic practice is a solitary pursuit. He also spoke of the influence of Warhol’s fascination with everyday culture, a sensibility that resonated with his own artistic leanings. “Andy may have been more…cynical than I am. But he took pleasure in the culture. He was just amazed at how things just are.”

Shore’s books have been crucial in disseminating his work and solidifying his reputation. “American Surfaces,” published in 1999, is a landmark publication, compiling many of his most recognizable images from the 1970s. The book is more than a mere collection of photographs; it is a meticulously sequenced journey through the American landscape, a visual narrative that unfolds with each page turn. “Uncommon Places” is another important collection of his large-format colour photographs. Shore explained that the 1982 edition of Uncommon Places was incomplete. “I knew that there were a lot more—I mean a lot more [photographs]—that ought to be in it.” The expanded edition includes a greater number of interiors and portraits, more accurately reflecting the range of his photographic interests during that period. “The original gave a false impression of what was going on in the work,” he said. He also discussed the book’s structure, noting that it is not strictly chronological but rather organized around distinct photographic trips. This structure was intended to highlight a stylistic evolution, which he believes is intrinsically linked to personal growth. The inclusion of portraits in the expanded Uncommon Places is particularly noteworthy. Shore explained that these portraits were not intended as in-depth character studies, but rather as “surfaces, as cultural artifacts.” He also pointed out that using a tripod for portraiture created a different dynamic with his subjects, allowing him to focus more intently on their expressions and the specific moment of the photograph. “I can pay more attention to them, because I’m not seeing them through a viewfinder, I’m seeing them with my eyes, and I’m choosing the moment just with my eyes, without a camera in between.” He also spoke about his “Conceptual work,” which explored serial imagery and systematic approaches to photography. He cited the influence of John Coplans’s Serial Imagery and his interactions with conceptual artists, while emphasizing his own background as a photographer and the importance of visual meaning in his work. “I thought I could bring something visual to a concept,” he explained.

Shore’s exhibitions have also been critical in establishing his place within the art world. His work has been displayed in major museums and galleries internationally, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Art Institute of Chicago. A significant retrospective of his work at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles in 2007 further cemented his position as one of the most significant photographers of his generation. These exhibitions have provided viewers with the opportunity to experience the breadth of Shore’s oeuvre, from his early snapshots to his more recent projects.

Shore’s work occupies a complex and nuanced position within the history of photography. He is part of a lineage of photographers who have explored the American landscape, from the 19th-century pioneers to the documentary photographers of the 20th century. However, he also distinguishes himself from these traditions, forging his own unique path. His use of colour, his focus on the quotidian, and his quiet, observational style have all contributed to a fresh way of perceiving the world.